National Recovery Guidance: common issues

Guidance primarily aimed at local responders covering some common issues that may arise during the Recovery Phase of an emergency in the UK.

Recovery structures and processes

Recovery is a complex and long-running process that will involve many more agencies and participants than the response phase. It will certainly be more costly in terms of resources and it will undoubtedly be subject to close scrutiny from the community, the media and politicians alike. It is therefore essential for the process to be based on well thought out and tested structures and procedures for it work in an efficient and orderly manner.

Policy and guidance

England

Non-statutory guidance on the multi-agency structures and processes that can be used during the recovery phase is given in ‘Emergency response and recovery’. However, recent emergencies have shown that local responders would benefit from access to more detailed guidance, hence the production of this National Recovery Guidance.

In addition, responders have indicated that having access to a generic recovery plan template would also be of assistance as they take forward their recovery planning. In light of that, a ‘Recovery plan guidance template’ has been drawn up using examples from many existing local authority recovery plans and the experience of those affected by events such as severe flooding and other major emergencies both in the UK and abroad.

The template provides generic guidance to assist in the recovery phase of emergencies. Depending on the scale or nature of the emergency, some parts may not be relevant and a flexible approach both to the emergency and recovery is needed. It is also important to bear in mind that if the event is regional or sub-regional in scope, this plan must, by necessity, be a part of the wider recovery process. Reference should be made to the contents of the Community Risk Register when producing the plan to ensure it reflects the hazards and threats in the local area.

The template has been developed to enable it to be adapted for use at different levels, - on a regional, local resilience forum (LRF) or local authority geographic footprint. Users can extract whatever content they feel is appropriate to their particular needs. For example, users may wish to develop a local authority-based generic recovery plan, and/or an LRF-based generic recovery plan, or incorporate a recovery chapter in an LRF-based generic major incident plan. There are no rules as to which approach should be taken, so long as:

- the resulting plan(s) is seen as fit-for-purpose by those multi-agency local responders who will need to use them

- plans are scalable and complementary, for example, if an emergency covers a wide area, all the recovery plans (and the structures and processes contained in them) must be capable of operating seamlessly, side by side, so the service provided to the affected community is consistent and joined-up

The template explains:

- the differences between response, recovery and regeneration, recognising there is often an overlap between them; the recovery process should start as soon as possible after the initial response, and run in parallel with it, until the formal handover from response to recovery takes place

- the purpose and principles of the recovery process

- an outline recovery strategy

- the various impacts that an emergency may have and the methodology of an impact assessment

- guidelines on handover from the response to the recovery phase

- a suggested structure diagram of a recovery co-ordination group (RCG); his is backed up by suggested terms of reference, group membership, and lists of potential issues for the RCG and its various sub-groups to consider

Wales

The template is equally applicable to Wales, where similar structures exist at the local level. However, responsibilities devolved to the Welsh Assembly must be taken into account in recovery planning.

Scotland

[TBC]

Northern Ireland

The principles and guidance set out above are relevant to Northern Ireland. However, the statutory and organisational context is different. ‘A guide to emergency planning arrangements in Northern Ireland’ and ‘The Northern Ireland civil contingencies framework’ set out contingency planning, including recovery planning arrangements for Northern Ireland.

The Local Government Emergency Management Group publication, ‘The role of district councils in emergency planning and response: support to other organisations’ provides information on some local recovery arrangements.

Roles and responsibilities

Local and regional - emergencies within one local authority’s boundaries

The local authority is the agency responsible for planning for the recovery of the community following any major emergency, working closely with other local and regional partners via the resilience forums.

Following an emergency, it will usually co-ordinate the recovery process, including by chairing and providing the secretariat for the RCG, with support from the full range of multi-agency partners as necessary. The recovery plan template provides details of those other multi-agency partners who may be involved in recovery and outlines their roles and responsibilities.

Local and regional - emergencies crossing local authority boundaries

When carrying out their recovery planning, local authorities, along with their local and regional resilience forum partners, need to agree how they would co-ordinate the recovery from emergencies that cross local authority boundaries. The agreed arrangements need to be detailed in the relevant local and regional plans.

Where the emergency crosses a local authority boundary but remains within one LRF area, the affected authorities will need to decide whether to establish one recovery co-ordination group (RCG) at the LRF level, or whether to operate separate RCGs in each local authority area. To ensure there is consistency of approach, no duplication of effort, and to reduce the burden on agencies that cover more than one local authority area, the recommended approach would be to have 1 RCG to cover all affected communities within the LRF area. In this instance, it would be sensible for the affected local authorities to designate a lead local authority that would provide the RCG chair and secretariat. Other local authorities could then provide deputy chairs as necessary.

Where the emergency crosses LRF boundaries, consideration should be given to the potential assistance that the Regional Civil Contingencies Committee (RCCC) could provide in ensuring consistency of approach, reducing duplication of effort, minimising the burden on responders, and facilitating the sharing of information, support and mutual aid. Reference should be made to the relevant generic regional response plan for details of how local authorities are represented at RCCC meetings.

Lead government department

In an event requiring national level recovery structures to be activated, the Civil Contingencies Secretariat (Cabinet Office) will decide the lead government department, based on the type of emergency.

The regional resilience team in the relevant government office will provide the conduit for communication with the nominated lead government department.

Other government involvement

Other government involvement in national level recovery structures will depend upon the specific emergency. Responsibilities will lie where they fall.

Devolved administrations

Where emergencies cross government (or in the case of Northern Ireland, country) boundaries, it is clearly still vital that recovery efforts are co-ordinated. However, it should be recognised that different legislation and funding streams, as well as different structures, may be in place in the devolved administrations. These are outlined further on in this guidance. Areas that border devolved administrations are encouraged in the planning phase to agree how recovery would be co-ordinated in cross-government boundary incidents and record this in the relevant local and regional plans.

Within the devolved administrations, the same recovery co-ordinating groups would be established. Equally, in place of RCCCs, the devolved administrations could establish their equivalents (Wales Civil Contingencies Committee for Wales, TBC for Scotland, TBC for NI) to fulfil the same role.

Wales

Many aspects of recovery fall within the devolved responsibility of the Welsh Assembly government in Wales, which will therefore act as the lead government department in those instances.

Scotland

[TBC]

Northern Ireland

Recovery planning for local emergencies would fall to district councils and other local organisations. For civil contingencies purposes Northern Ireland district councils (other than Belfast City Council) work in groups. The local government emergency management group (LGEMG) co-ordinates civil contingencies activities across district councils and other organisations. Arrangements are in place for councils to decide quickly on a lead council for local emergencies which cross council or group boundaries.

District Councils which border the Republic of Ireland have arrangements with local authorities across the border for dealing with any local incidents which cross the border.

In emergencies with a regional dimension a lead government department or the Northern Ireland central crisis management machinery would co-ordinate response and recovery, although local organisations would still have a significant role to play at community level.

In regional emergencies with a cross border dimension, the Northern Ireland Executive would work closely with its counterparts in the Republic of Ireland to ensure a co-ordinated approach to response and recovery.

Funding

Local authorities are expected to fund and carry out recovery planning through their normal emergency planning workstreams.

Case Studies (Incidents and Exercises)

Other Useful Documents

Focus on Recovery: A holistic framework for recovery in New Zealand

List of Contacts

[TBC]

Training and exercising

Background and Context

Emergency Preparedness makes clear the need for training key staff to obtain the necessary competence (which is a combination of knowledge, skills, and attitudes) as well as running exercises to test the robustness of plans. The distinction lies in differentiating between the competence of responders and the effectiveness of the plan so that these can be assessed.

Training for the recovery phase and validating the arrangements through exercises is less developed than our ability to train and exercise for the response phase of an emergency. However many of the processes are the same, it is just that the context is different, often delivered over a much longer time line, and involves a wider group of stakeholders.

National Occupational Standards (NOS)

National Occupational Standards (NOS) describe competent performance in terms of outcomes of an individual’s work and the knowledge and skills they need to perform effectively. The NOS for Civil Contingencies allow a clear assessment of competence against nationally agreed standards of performance, across a range of workplace circumstances for those involved in resilience and civil protection. For further information, please visit www.skillsforjustice.com.

Core Competences Project

The Core Competences Project was initiated as a joint venture between the Cabinet Office Emergency Planning College and the Emergency Planning Society. One year into the Project it was announced that the Sector Skills Council for Justice would be leading a project to develop NOS in Civil Contingencies. Consequently, it was agreed that Skills for Justice would work in partnership with the Project and as a result the NOS for Civil Contingencies form the foundation of the Core Competencies Framework.

The resulting Framework has been designed to cover those areas that are considered to be essential to the practice of emergency management. The eight technical areas of the NOS for Civil Contingencies which form the foundation for the Framework have been extended to include four further areas of competence:

- theories and concepts in emergency management

- acting effectively across your organisation

- debriefing after an emergency, exercise or other activity

- managing computer generated data to support decision making

Policy and Guidance

England

Firstly, to clarify the distinction between training and exercising - Emergency Preparedness suggests:

Training, as such, as distinct from exercises, is broadly about raising the awareness of the participants (who are those named in the plan or mobilised by it) about what the emergency is that they may face and giving them confidence in the procedures and their ability to carry them out successfully. It is particularly important that participants in training understand the objectives of the plan and their part in achieving them. [Paragraph 5.134 of Emergency Preparedness]

Generally, participants in exercises should have an awareness of their roles and be reasonably comfortable with them, before they are subjected to the stresses of an exercise. Exercising is not to catch people out. It tests procedures, not people. [Paragraph 5.143]

Having made the distinction above, there is an overlap between the two:

Exercises have three main purposes:

- to revalidate plans (revalidation)

- to develop staff competencies and give them practice in carrying out their roles in plans (training)

- to test well established procedures (testing)

Most exercises will have some elements of all three. [Paragraph 5.144]

Training

In order to develop a Recovery capability, it is essential that roles, responsibilities and procedures have been identified and that the people involved have the necessary competence. Competence can be defined as having the appropriate knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSA). The level of competence needed has to be defined, then an assessment carried out of what level of competence the people responsible for delivering the capability currently have. This process is called a Training Needs Analysis, and should follow the same approach as that which is used to identify training needs for the response phase.

The stages involved in a Training Needs Analysis are:

- Detail what is needed to deliver the capability.

- Detail who is responsible for delivering the Recovery capability in terms of organisations and positions / roles within it. This should flow from the multi-agency Recovery Plan and include Category 1 & 2 responders, plus anyone else needed to deliver the capability including members of the voluntary and private sectors.

- Detail what competences (KSA) these different people need in order to deliver the different elements of the capability including planning for and implementing the Recovery plan. Also include the competences they need at the individual, team and multi-agency level.

- Assess current competences and current training provision (including exercising, guidance, literature, etc. and training providers). Having completed stages 1 – 3 above, what competences are needed and by whom should be apparent. This will enable questions to be designed to assess current competence in the areas required. Current competences and current training provision can be identified through a number of methodologies such as:

- questionnaire – sent to people involved in preparing for and delivering the capability

- focus groups (facilitated sessions using people from different levels and different organisations)

- structured interviews (1 to 1) with policy leads and / or operational staff

- unstructured interviews with experienced personnel to gather more thoughts / suggestions / clarification

The competences required during the recovery phase are more likely to be aligned to the day-to-day role of responding staff. For example, in dealing with people made homeless during an emergency, it is expected that local authorities will primarily use staff that deal with homelessness issues on a daily basis – albeit maybe not to the scale or in the timescales expected following an emergency. This approach to allocating people to tasks not only effectively builds on their existing knowledge of the subject area, but also enables them to use their probably well developed network of contacts both within the local authority area and further afield, which may be particularly helpful if mutual aid is required.

Exercises

Whilst there is generic guidance in Emergency Preparedness and the Home Office Exercise Planning Guide on designing and running exercises, there is no specific guidance on exercising the recovery phase.

The Civil Contingencies Secretariat is currently developing and bringing together a range of exercises, guidance and support tools [‘tools’ here is meant in the broadest sense, meaning specific tools and techniques and more general frameworks and guidance] which could be used to assist organisations in exercising recovery and which may then be used to inform planning for recovery.

The tools are designed to provide support and accompanying materials to facilitators in exercising recovery. Completed documents and tools can be found below.

Partner exercise: Click on the hyperlinks below to access material for using the Partner Exercise:

The tools here form part of a planned wider package which will be used to provide further guidance on exercising recovery. Further tools will be added to this site. These will include, amongst others, suggested injects and scenarios for a recovery exercise, and decision tools.

These tools have been developed by the Civil Contingencies Secretariat, with the assistance of the Recovery Exercising Advisory Group (REAG). REAG consists of representatives from:

- Communities and Local Government

- Coventry City Council

- Emergency Planning College

- Environment Agency

- Essex Fire and Rescue Service

- Food Standards Agency

- Government Decontamination Service

- Government Office North West

- Health Protection Agency

- Lancaster University

- Local Government Association

- North Wales Resilience Forum

If you wish to be involved in this Group or for more information on this work, please contact recovery@cabinet-office.x.gsi.gov.uk.

Many organisations have run recovery exercises. Case studies from recovery-related exercises can be found at the bottom of this page. The learning from these has shown that:

- In light of the cross-cutting nature of recovery, as wide a range of participants as possible should be involved in recovery exercises. This will go beyond the usual ‘resilience family’, and may include bodies such as Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs), Tourist Boards, Chambers of Commerce, Natural England, or English Heritage (and devolved equivalents in devolved areas), as well as community groups and faith leaders, and possibly even individual businesses. Similarly, other wider representatives from Category 1 and 2 organisations, such as Social Services and Elected Members from local authorities, should also be encouraged to attend. Invitation lists can be compiled based on those organisations detailed in the Recovery Plan. It is important that exercises are written to cover issues relevant to all organisations present, or else attendees may feel they have not benefited from attendance, and it may be difficult to obtain their input at future events.

- It is difficult to reflect the true nature of recovery in an exercise, as exercises normally only last for a day or two, whereas the recovery phase itself can of course last for one or two years. There are a number of ways in which this can be overcome, for example:

- by holding a number of exercises to represent various stages of the recovery phase. These may be split by time (eg. starting at day 5 after the emergency has occurred, then jumping to 2 weeks after the emergency, then 2 months, and so on), or by key milestones (eg. prior to clean-up, once clean-up is complete, etc).

- by running one exercise but using ‘time-lapse’ at points during the day. Again, the exercise can be split by time or key milestones.

- Whatever approach is used, there needs to be comprehensive pre-start briefing which summarises the scenario to date and the decisions that have been made in the response phase. This will help ensure that people do not become focussed on response issues during an exercise that is supposed to be focussed on recovery. Consideration should therefore be given to running recovery exercises on the back of response exercises to avoid this tendency taking place.

- There is considerable benefit in exercising the handover phase from response (Strategic Co-ordinating Group) to recovery (Recovery Co-ordinating Group) so that the criteria that would be used to determine the right time for handover to take place and the handover processes themselves can be tested. This aspect can clearly be covered in both response and recovery exercises.

- As with response exercises, the scenarios used in recovery exercises should be prioritised in line with the key risks in the Community Risk Register. However, Local Resilience Forums may wish to ‘tweak’ scenarios to ensure they test out those particular aspects of recovery which have been found to be weak / a gap in incidents and exercises elsewhere.

- The use of scenarios that result in recovery co-ordination being required across local authority / LRF boundaries are encouraged in order to test out the effectiveness of cross-boundary recovery structures and processes.

- Testing mutual aid arrangements, particularly between local authorities, is beneficial.

- Issues identified in recovery exercise debrief reports that would be of interest to partners outside of the LRF area should be shared with Regional Resilience Teams (or devolved equivalents) for wider dissemination.

Wales

The Wales Resilience Forum is overseeing the development of a Wales exercise and training programme through its multi-agency Wales Training and Exercising Group. A central training fund has been established for pan-Wales training and exercising which is managed by the group.

All four Local Resilience Forums in Wales have exercised their recovery plans in recent years all of which have used a flooding scenario: Exercise Rufus (Dyfed-Powys), Exercise Rufus II (South Wales), Exercise Watertight (North Wales) and Exercise Ursula (Gwent).

Scotland

At a national level, the Scottish Resilience Development Service of the Civil Contingencies Unit is responsible for civil contingencies training and exercising. The Service has produced Scottish Exercising Guidance – July 2009 which provides generic guidance on exercise management and which aims to set out good practice for all forms of civil protection exercises in Scotland, including those that deal with recovery issues.

The Service has developed a system for exercise management, including a database of exercises available to registered users. For further information, see https://scords.gov.uk/.

Individual training for recovery management is primarily a matter for mainstream learning providers. For example, those carrying out environmental protection activities during the recovery process should develop their competence through mainstream environmental management training and development.

Collective training may be needed to ensure that teams are able to put their skills into practice in an emergency. Organisations that are members of Civil Contingencies Strategic Co-ordinating Groups are responsible for making sure team members are aware of their role throughout an emergency and have the opportunity to try out their skills, for example through exercises. Responder agencies may also use exercises to both evaluate arrangements and performance. Such exercises should follow normal good practice.

Northern Ireland

No differences for Northern Ireland.

Roles and Responsibilities

Local and Regional

Training of key staff is the responsibility of their respective organisations, although there is merit in considering the use of multi-agency training events to cover the various aspects of recovery.

Local authorities will usually lead on the development, implementation and debrief of recovery exercises, but this should be with the full support of all Local Resilience Forum members and wider partners.

Lead Government Department

Cabinet Office co-ordinate the cross-government exercise programme.

The Emergency Planning College – part of the Cabinet Office – run training events on recovery.

Other Government Involvement

Many departments who have a Lead Government Department role for particular capabilities / scenarios run national exercises. These have tended in the past to focus on the response phase of incidents, but departments have run some specific recovery exercises and the recovery phase can be built in to response exercises.

Regional Resilience Teams co-ordinate a regional exercise calendar. Recovery training and exercises should be fed into these programmes, as with all other Local Resilience Forum events, to avoid diary clashes and facilitate the identification of possible cross-LRF training and exercising opportunities.

Devolved Administrations

Wales

The Wales Resilience Forum oversees the development of a Wales exercise and training programme through its multi-agency Wales Training and Exercising Group.

Scotland

No difference

Northern Ireland

The Emergency Planning College has a new prospectus for Northern Ireland. The training is delivered locally by Emergency Planning Solutions who are accredited by the college to deliver EPC training within the Province.

Funding

The funding for any training is expected to be absorbed internally within the relevant organisation.

Recovery exercises are usually funded by the local authority, but contributions may be sought from all participating organisations.

Devolved Administrations

Wales

Funding of exercises at the local level in Wales is generally handled through the Local Resilience Forums. A central training fund has been established for pan-Wales training and exercising which is managed by the Wales Training and Exercising Group.

Scotland

[TBC]

Northern Ireland

[TBC]

Case Studies (Incidents and Exercises)

Other useful documents

- UK Financial Sector’s market-wide exercise 2009 final communiqué 4

List of Contacts

- The Emergency Planning College runs courses on recovery and is also able to offer further advice and guidance about developing and implementing a training strategy.

- Scottish Resilience Development Service

- Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development

- Emergency Planning Society Competency Framework

- National Occupational Standard

Data protection and sharing

Background and Context

Data protection and data sharing have long been issues for the public and private sectors. In a number of emergencies, problems, either perceived or real, surrounding interpretation of Data Sharing and related Human Rights legislation have prevented public bodies from carrying out their duties effectively. The Indian Ocean Tsunami, the Bichard Inquiry (into the Soham murders) and the Victoria Climbie Inquiry all identified areas of uncertainty in the interpretation and application of data protection and sharing rights and responsibilities.

Most recently, as part of the government’s lessons identified programme following the 7 July 2005 London bombings, it was found that limitations on the sharing of data between a number of Category 1 and 2 responders hampered the connection of survivors to appropriate support services. Subsequent investigation found that many of these limitations were self-imposed and resulted from incorrect application of duties perceived to be imposed on public organisations by the Data Protection Act and other legislation.

Data sharing within and between the public and private sectors, and between Category 1 and 2 responders, cuts across a range of scenarios and responsibilities – the duty to properly risk assess at local and regional levels; to construct effective and realistic emergency plans; during the response to an emergency; and to recovering from and managing the consequences of emergencies.

Policy and Guidance

England

The range of guidance available, reflect that this is an issue that cuts across all workstreams and the public/private sectors at national and local levels. Guidance touches on many roles and responsibilities, from legal powers of local authorities, to the detailed restrictions on the sharing of medical histories, through to the sharing of utilities data to aid in risk assessment.

- Data Protection and Sharing – Guidance for Emergency Planners and Responders

- Government’s Vision for Information Sharing

- The DCA Toolkit for Data Sharing and Data Sharing Library

- Information Commissioners’ Office (ICO)

- Data Sharing Review

Patient Confidentiality and Access to Health Records

There are significant differences between sharing certain types of personal data (name and address for example) and sensitive personal data (health details for example), and both the Cabinet Office guidance on data sharing in emergencies and DH guidance make this clear.

Recent experience has clearly indicated that compiled and refreshed guidance is needed. Both the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) and the Ministry of Justice are developing complementary guidance on data sharing and protection issues that takes account of experience, case history, and balancing the needs of the general public and public and private organisations.

Devolved Administrations

Data sharing is a pan-UK issue. The Data Protection Act itself applies to the entire UK. The Civil Contingencies Act covers the UK, but with differences in the responsibilities placed on devolved administrations. However, the underlying principles of a pragmatic, sensible and balanced approach to data protection and sharing are universal.

Roles and Responsibilities

Local and Regional

Category 1 and 2 responders have a duty under the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 to share information to aid resilience planning, response and recovery. This obviously necessitates an understanding of the relevant legislation and the responsibilities of those requesting and those providing information. Both public and private sector organisations are bound by the Data Protection Act and related legislation.

Lead Government Department

In relation to enhancing resilience capabilities, data sharing comes in two parts – pre-emergency, mainly for planning purposes, and post-emergency, mainly for providing support services. The Lead Government Department indicated below can offer advice where relevant, but in an emergency, responders should be prepared to make a decision without formal advice.

The Lead Government Department for the Data Protection Act and the Human Rights Act is the Ministry of Justice.

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) is the independent authority set up to promote access to official information and to protect personal information. The remit of the Information Commissioner includes the Data Protection Act and the Freedom of Information Act amongst others. Whilst their main role is to protect and promote the public’s interests, the ICO can offer a view on specific cases.

Other Government Involvement

Cabinet Office (in the form of the Civil Contingencies Secretariat - CCS) co-ordinated the publication of Data Protection and Sharing – Guidance for Emergency Planners and Responders, and are owners of the lesson identified from the 7 July London attacks. Information relating to the Civil Contingencies Act and information sharing can be found on the Information and Data Sharing page.

Case Studies (Incidents and Exercises)

List of Contacts

- The Ministry of Justice helpline to answer urgent queries on the Data Protection and Human Rights Acts is 020 7210 8034 or www.dca.gov.uk/ccpd/lcdcontacts.htm

- Information Commissioner’s Office for online enquiries Helpline 01625 545745

- Civil Contingencies Secretariat

Mutual aid

Background and Context

Successful response to emergencies in the UK has demonstrated that joint working and support can resolve very difficult problems that fall across organisational boundaries. Large scale events have shown that single organisations acting alone cannot resolve the myriad of problems caused by what might, at first sight, appear to be relatively simple emergencies caused by a single source.

Mutual Aid can be defined as an arrangement between Category 1 and 2 responders and other organisations not covered by the Act, within the same sector or across sectors and across boundaries, to provide assistance with additional resource during an emergency, which may overwhelm the resources of an individual organisation [Emergency Response and Recovery].

Civil Contingencies Act

Bi-lateral and Cross Border Co-operation

Although the Act lays down duties regarding bi-lateral co-operation, that should not be seen to restrict responders working closely together outwith its provisions. For example, it would be anticipated that adjacent local authorities in differing police force areas would co-operate in matters of mutual interest in the same way that their respective SCGs/LRFs would. In this way, good practice can be identified and shared across boundaries.

Joint discharge of functions

In some instances, Category 1 responders may wish to go beyond bi-lateral co-operation and enter into formal joint arrangements with other Category 1 responders. Care should be taken to ensure that joint arrangements have taken into consideration the needs of all partners which might have an interest in the arrangements being made. Failure to accommodate the needs of all partners will prove both wasteful and inefficient, and ultimately will undermine the benefits of local partnership working.

UK Policy and Guidance

While there is no UK wide policy specifically relating directly to mutual aid, many areas such as police, fire, NHS and local authorities have inter (and intra) agency mutual aid protocols in place. Most of these are formal, but many are informal.

Formal protocols detail how each partner will undertake or allocate responsibilities to deliver tasks. Protocols may cover matters of broad agreement or details for working together, including how to hand over tasks or obtain additional resources. Protocols may or may not be legally binding depending upon the nature of the agreement between the parties.

The Local Government Association and Civil Contingnencies Secretariat are currently undertaking a project to provide support and guidance to enable local authorities to develop effective mutual aid arrangements. This work will be informed by the Sir Michael Pitt Flood Review. More information on the project’s outcomes will be made available as the project progresses.

A significant part can be played by the voluntary sector and others - partnerships may also embrace a wider group of organisations at the appropriate level. For example, WRVS and the Red Cross may work with local authority social services to open rest centres and deal with the needs of displaced people, and local businesses might work with the emergency services regarding evacuation plans for a shopping centre. The National Voluntary Sector Civil Protection Forum, in partnership with the Civil Contingencies Secretariat, has produced a , which provides some suggestions to support Category 1 responders’ and their voluntary sector partners’ work when considering collaborative arrangements.

Local emergency plans should take into consideration the possible requirement for assistance which may be outwith the local government sphere and these should be fed into the plans themselves. As well as the voluntary sector, there may be a need to work with other organisations such as utilities and transport providers, and it is good practice to make contact with these organisations and maintain links with them to make the contact easier in the event of an emergency.

Local authority mutual aid guidance

The Civil Contingencies Secretariat in collaboration with the Local Government Association (LGA) and the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives and Senior Managers (SOLACE) has produced a short guide to support local authorities in developing effective mutual aid arrangements. The guide offers advice on a range of practical considerations and provides a general framework that can be developed by authorities to satisfy local requirements. Publication of this guide meets Recommendation 38 of Sir Michael Pitt’s report on the 2007 floods.

Mutual Aid - A short guide for local authorities

Co-ordinate Offers of Material Help

It is likely that many offers of help will arrive from the general public, businesses, charities, voluntary agencies and others both during the response and recovery phase. Some will be of practical assistance, others goods for those directly affected.

Consideration should be given to:

- procedures to register and co-ordinate offers of help

- forming a panel to assess needs and the distribution of donated help

- identifying storage areas

- a disposal mechanism for unused donations

Roles and Responsibilities

Local and Regional

Local Resilience Forums (LRFs) ensure effective delivery of those duties under the Civil Contingencies Act that need to be developed in a multi-agency environment including the recovery aspects. LRFs can also facilitate the provision of formal mutual aid agreements between its members.

Regional Resilience Forums (RRFs) can also be used for facilitating wider mutual aid agreements, eg. between all Local Authorities in a region.

Mutual Aid arrangements exist within and between many of the voluntary sector organisations, for activation as required, particularly across boundaries. In the event of a major or international emergency, voluntary sector support may be accessed through the head offices of the relevant voluntary organisations or through the Voluntary Sector Civil Protection Forum or the National Voluntary Aid Society Emergency Committee (NVASEC).

Links with the voluntary sector will normally be co-ordinated through the Local Authorities in an area - often through a sub-group of the Local Resilience Forum – and activation and co-ordination arrangements for voluntary sector involvement in both response and recovery phases should be formalised as part of emergency planning work.

Lead Government Department

There is no lead Government Department for the co-ordination of mutual aid arrangements, although dependent on the emergency, it may be possible for the relevant government department to assist with the facilitation of mutual aid.

Other Government Involvement

Departments involved will be determined by the type of incident that has occurred.

Devolved Administrations

Scotland

Strategic Co-ordinating Groups are established in each of the Police Force areas and include amongst their roles, to ensure co-operation, mutual assistance and support for local responders. Where an emergency demands significant police involvement, the Scottish Police Information and Co-ordination Centre (S-PICC) can be activated to support SEER by collecting information from Scottish police forces, and to co-ordinate mutual aid between police forces.

Wales

As in England, the LRFs can oversee the provision of formal mutual aid agreements between their members whilst the Wales Resilience Forum can facilitate such arrangements on a broader basis.

Finance

Detail on the financial implications of any mutual aid agreement should be determined between the parties and set out within the protocol.

Case Studies (Incidents and Exercises)

Other Useful Documents

There are many examples of mutual aid protocols available. Below is a selection:

- Fire Service National Mutual Aid Protocol for Serious Incidents

- British Transport Police and Scottish Police Forces Policing Protocol

- Co-ordinated Policing Protocol between the British Transport Police and Home Office Police Forces

Military Aid

Background and Context

Whilst the Armed Forces have provided ad-hoc assistance to the civil authorities on all manner of occasions over the years, resilience planners must not assume that such support will be available in the future when developing their capability programmes. Military support is provided on an assistance basis and a variety of factors means that it cannot be guaranteed.

The Ministry of Defence has a share in the wider Government responsibility for the safety and security of the citizens of the UK. That contribution, however, rests crucially on its ability to undertake expeditionary operations, including the ability to undertake expeditionary counter terrorist operations and capacity-building. The security of the UK depends on the Armed Forces ability to undertake such tasks, and operations in the UK must therefore be regarded as exceptional and unusual. Military Assistance to the civil Authorities (MACA) can, however, make a significant contribution at times of extreme crisis, and the Armed Forces will remain prepared to respond to some emergencies in the UK, especially where Defence can achieve a strategic effect. Defence will continue to work to enhance and support the capability, capacity and confidence of civil agencies in responding to such challenges with the minimum of disruption to the lives of the ordinary citizen.

During a Recovery/consequence management operation the provision of Armed Forces’ support will require the approval of a Defence Minister following the receipt of a formal request by a government department

Policy and Guidance

The Armed Forces remain heavily committed to operations overseas and are likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. Those parts of the Armed Forces that are not currently employed on operations overseas are largely preparing for, or recovering from, such operations. There is little spare capacity to carry out additional tasks.

The framework for MOD involvement in the consequence management of civil contingencies in the UK is therefore one of civil primacy, civil capability and civil capacity. Case-by-case assistance to the civil authorities is possible through the Standing Home Commitments Group of Military Tasks but resilience and recovery planners must understand that planned Defence contributions at home are very much by exception, in particular where it is unreasonable or unrealistic to expect the civil authorities to develop their own capabilities.

If available, Defence capabilities held for overseas tasks may be called upon to support the Civil Authorities providing there is no civil alternative; if the capability and/or capacity of the civil sector is overfaced; and they do not duplicate the efforts of other agencies and departments.

The Armed Forces have provided assistance on this basis to a number of other Departments and Agencies over the years and can be called upon in extreme and unusual circumstances to provide support to the civil authorities. However, historical evidence of Defence assistance for a particular role is no justification for similar requests. Moreover, it should not be planned for the Armed Forces to fill gaps in civil capability or capacity: where a gap in civil capability can be identified in advance, it is for resilience planners to fill that gap.

It is accepted that during an emergency, unforeseen failures of the resilience plan or events in excess of planning assumption, will generate requests for Military aid. Planners should bear in mind that Defence’s priority will be focused on delivering Defence outputs. Any requests will be scrutinised in terms of Military capability and capacity available and whether the actual request is a good use of Military assets - a positive response is not guaranteed. For instance, should Defence contribute to the delivery of security and public order or should they be utilised for municipal tasks; this will be a decision for ministers.

Armed Forces support to civil resilience can be divided into two categories:

- Niche capabilities. Where, in the view of Defence Ministers, it is in the national interest to devote specific Armed Forces and MOD assets to specific operations in the UK, either in whole or in part. These assets are identified in Defence Planning Assumptions and are guaranteed. They include: * a UK-based and UK-focussed Command and Control structure * a UK focused Defence communications capability * an Explosive Ordnance Disposal and Chemical Biological Radiological and Nuclear make-safe capability * an air surveillance, policing and defence system * Fishery Protection vessels * a Special Forces capability * a Search and Rescue capability

- Augmentation Capabilities. When civil contingencies arise, it is possible to deploy the armed forces in support of the civil authorities if Defence Ministers consider it appropriate. Resilience planners should not make assumptions about the criteria that might influence a Defence Ministers decision in advance and should not make assumptions about the level of military deployment. Defence Ministers will only be able to draw on the forces available at the time and this will depend on the degree to which the regular and reserve forces were committed overseas. However, it is safe to assume that deployment of the Armed Forces in this role would not normally be considered unless the deployment was required to make a strategic impact on extreme and unusual circumstances.

The legal basis for instructing Armed Forces personnel to provide support to the civil authorities in the UK can only be one of the following:

- Section 2 of the Emergency Powers Act 1964 (plus the Emergency Powers (Amendment) Act (Northern Ireland) 1964) which enables the Defence Council to issue instructions to undertake ‘work of urgent national importance’

- Part 2 of the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 which enables the Queen or a Senior Minister, in particular circumstances, to issue emergency regulations which can in turn enable the Defence Council to deploy the Armed Forces

- tenet of common law indicating that citizens should provide reasonable support to the police if requested to do so. All members of the Armed Forces have a duty to provide the support normally expected of the ordinary citizen. The same common law tenet enables a Defence Minister to direct the Armed Forces, on a case by case basis, to provide specialist support to the police

Military units and personnel remain under the MOD chain of command at all times and are not subordinated to the command of civil authorities.

Devolved Administrations

Provision of MACA remains a central issue.

Roles and Responsibilities

Local and Regional

Personnel of the police and other civil agencies are granted special powers unique to them. To ensure that they are even-handed in the application of these powers, they are operationally independent of Government. Local agencies have the authority to institute local responses.

The Armed Forces are not independent of Government and Armed Forces personnel do not have additional powers granted to them. They remain under Central Government control at all times and only Defence Ministers can authorise their deployment, for any purpose. Support to the civil authorities cannot be provided without this authorisation. This also means that provision of Military Support automatically involves the elevation of the response to central Government.

In the first instance, guidance on requesting military aid for recovery situations should be sought from the Joint Regional Liaison Officer (JRLO) who is a key member within the LRF / RRFs. The JRLO can then liaise with the appropriate Defence Organisations to seek further advice. JRLO liaison involves the provision of advice and the exchange of information. It does not guarantee the provision of support. However, any formal request must be made through the appropriate Government Department or Agency who will then approach the Ministry of Defence directly. It is worth noting that the armed forces are more likely to be engaged in the response to, rather than the recovery from, a crisis. Recovery is largely a local-authority-led task which requires planning of a nature where commercial alternatives might be found for the majority of tasks.

Lead Government Department

Ministry of Defence

One of the principal responsibilities on any government is the defence of the realm. The UK Government distinguishes between the defence of the UK against external military threats and the safety and domestic security of the citizen. The latter is the responsibility of the Home Secretary; the former the responsibility of the Secretary of State for Defence.

The principal purpose of the Armed Forces is to deploy armed force on behalf of the state. The bulk of the Armed Forces capabilities are therefore held at varying degrees of readiness to maintain the ability to engage security threats before they reach the UK, and are configured and held at readiness for contingent operations overseas. The function of the MOD is to ensure the continuing availability of these forces, to command and control them, to organise their deployment and support and to carry out a range of associated Department of State functions. The Armed Forces are not resourced for tasks in the UK, except for very specific exceptions, and few capabilities are held for tasks in the UK.

Funding

The emphasis on the role of the Armed Forces overseas is reflected in the Government’s allocation of resources to defence and to MOD’s own priorities, planning assumptions, force structures, strategic direction and operational tasking. Responsibility for security in the UK is widely shared between agencies and departments, and so too is the funding of that responsibility. The Defence budget should not be seen as a means of providing financial support to the activities of other agencies, no matter how worthy. Doing so would divert resources from defence activity.

MOD Ministers can decide that it is in the national interest to waive all or part of the costs, but this should be seen as exceptional. In particular, it should not be assumed that the distinction between niche and augmentation capabilities has any direct impact on whether or not MOD is prepared to waive costs. In some cases MOD is only prepared to provide niche capabilities on the understanding that other Departments or agencies are prepared to fund all or part of the costs.

Case Studies (Incidents and Exercises)

Historical events should not be used as evidence to approach MoD for Military assistance. Any request will be considered on its individual merits.

Other Useful Documents

Operations in the UK: The Defence Contribution to Resilience

List of Contacts

Working with the media

Background and Context

The impact of the media during a crisis cannot be underestimated. However, while during the height of an emergency there is likely to be widespread coverage, media coverage during the recovery phase can be more of a challenge.

During recovery from an emergency, there are often public information messages as important as during the height of the emergency, yet the media interest may have waned or moved onto other issues. Conversely, the need to get information out to the public involved remains. The continued involvement of local media will therefore be very important at this stage.

Policy and Guidance

England

- (the statutory guidance which supports the Civil Contingencies Act) and (the non statutory guidence to the Act) contain a wide range of guidance on communicating with the public and working with the media at, and during, an emergency.

- The BBC’s Connecting in a Crisis is an initiative to help ensure that the public has the information it needs and demands during a civil emergency.

Devolved Administrations

The same issues will apply throughout the UK.

Roles and Responsibilities

Local and Regional

In common with the response to the emergency itself, it is possible that different organisations many take the media lead for the response and recovery phases. For example, the police or other emergency service may be in the lead during the response, but the recovery phase may be led by the local authority.

If there is more than one organisation involved, one area that cannot be overemphasised is the need for co-ordination and co-operation between organisations in the move from response to recovery. This ensures that while, on the one hand, the continued involvement and contact with the media appears seamless, on the other hand, there is a clear emphasis that recovery is now being led by another organisation

As a situation moves towards the recovery phase, the national media interest is likely to be confined to very significant milestones or specific events – the publication of a report or an anniversary, for example. It is at this stage that the local media’s already significant role may become even more important.

During the recovery phase, the focus of the media will be on a number of specific areas – responsibility, costs, support for those involved, how organisation are rebuilding their business, how communities are coping.

Working with them to ensure that all this information is communicated could be through a wide range of options from special programmes, or slots on local radio or television programmes, to inserts in local papers – all have a role to play.

The Regional Media Emergency Forum (RMEF) will also have a role to play. The RMEF brings together a wide range of organisations – local authorities, emergency services, the Government Office, and Government News Network, to name but a few, as well as representatives from media at a local level. While their role has been mainly to establish what arrangements are required to ensure the delivery of information to the public in an emergency, they have also played a very important role in examining how to ensure that the co-ordination and information flow can be improved.

Lead Government Department

The Lead Government Department for the media response during the recovery phase may not be the same as that during the response phase. Close co-ordination between Departments’ communication teams is therefore very important and the Cabinet Office may well be involved in co-ordination of this work.

The Government News Network (GNN) is a government agency consisting of a national network of media professionals employed to assist all responders obtain the latest and best information, and to gather information for national media briefings. Whilst the GNN’s first responsibility is to the main Category 1 responder, it can help other local responders get out their key messages.

The small size of the teams make them most effective at regional tier level, but, depending on the emergency, may be able to deploy more locally by using other staff from other regions as a back office. Whilst the lead Department for the emergency will be responsible for picking up most of the GNN bill, other Agencies deciding to use GNN in an emergency may incur a cost at some point.

Other Government Involvement

It is important to note that the media will not only address questions to the Lead Government Department, but will also approach, for comment, a wide range of Government Departments and other organisations.

Depending on the nature of the emergency, it is also possible that the Government’s News Co-ordination Centre may be activated, and its role will be to ensure that the Government’s messages are co-ordinated with all departments and stakeholders.

The national Media Emergency Forum also have a role to play in ensuring that the role of the media during the recovery phase continues to be an important part of the overall communications package.

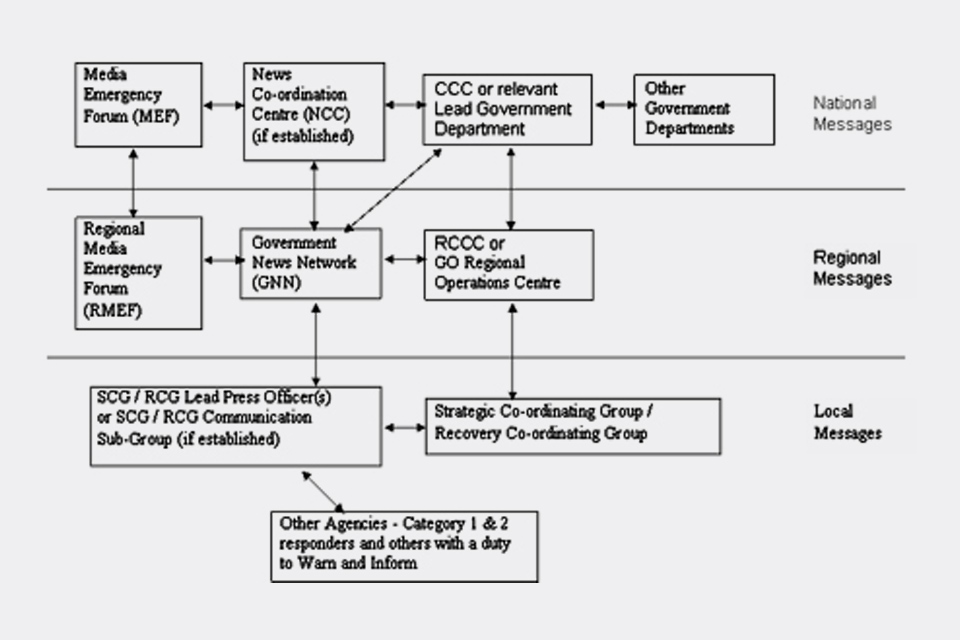

The following diagram illustrates the communication flows described above:

Diagram showing communication flows between National messages, regional messages and local messages.

Devolved Administrations

These issues apply in all areas of the UK.

Wales

In Wales, the Welsh Assembly Government will have a role to play in the co-ordination of the media handling strategy across Wales in close collaboration with the relevant Local Resilience Forum(s).

Scotland

[TBC]

Northern Ireland

[TBC]

Case Studies (Incidents and Exercises)

List of Contacts

The role of Elected Members

Background and Context

Recovery is usually led and co-ordinated by the local authority with support from a number of other partners.

As community representatives and figureheads in their local community, elected members for the affected community have an important role to play in assisting with the recovery process. Although they have a limited role in the operational response phase, the role of the local authority’s elected members is vital to rebuilding, restoring, rehabilitating and reassuring the communities affected and speaking on their behalf.

Roles and Responsibilities

Elected Members

Roles which elected members can play a part in include:

During the planning stages:

Elected members can play a key role both during recovery planning and during the actual recovery phase following an incident. During the planning phase, they can play a role in:

- promoting and encouraging the preparation of community plans

- by using their local knowledge to identify local groups and partners who may be able to play a role in recovery

During the recovery phase of an incident:

Listening to the community

As an elected representative for the area and local figurehead, elected members have a key role as the voice of the community. They are important in:

- being the eyes and ears ‘on the ground’ by providing a focus for and listening to community concerns

- being the voice of the community by gathering the views and concerns of the community and feeding them into the recovery process, through the Recovery Co-ordinating Group’s (RCG) Community Recovery Committee (see diagram below)

- providing support and reassurance to the local community, by listening or visiting those affected and acting as a community champion and supporter

Using local knowledge

As a member of their community, elected members have access to the thoughts, opinions and information relating to their local community. As such, they can play a part in:

- using their local awareness of the thoughts and feelings of the community to identify problems and vulnerabilities the community may have and which may require priority attention and feeding them back to the relevant recovery sub-group

- using their local knowledge to provide information on local resources, skills and personalities to the relevant recovery sub-group. Elected members are also often involved in other aspects of community life such as local community groups which can also be an important source of help and specialist advice. Working closely with community groups, elected members will also be valuable in knowing how and who is active within a community

Providing support to those working on recovery

- providing encouragement and support to recovery teams working within their community

- communicate key messages, from the RCG and its sub-groups, to their communities, disseminating accurate, credible advice and information back to the community and keeping community members involved, including potentially assisting in debrief sessions with the community and managing community expectations in tandem with the local authority

- actively engaging with community members involved in the recovery efforts and in community resilience work more widely

- promoting self-resilience within the community and managing residents’ expectations

Political leadership

- providing a political lead on the way in which decisions are made

- providing strategic leadership. Elected members have a role as committee members within their normal local authority duties and in doing this, give strategic direction and decide policy. They scrutinise decisions of officers and other committees and suggest improvements. As Cabinet Members, elected members will be involved in making key policy decisions and may have to consider recommendations from the RCG on strategic choices. Councillors have a constitutional duty to share corporate responsibility for local authority decision making.

- providing representation to Government for additional resources and financial assistance

- promotion of joint working with Parish, City and District authorities

- liaising with other elected representatives (MPs/AMs/MSPs/MLAs/MEPs/other LA representatives, etc)

- representing their community in the strategic Community Recovery Committee where relevant (see diagram above)

- ensuring recovery issues are mainstreamed into normal functions

- scrutiny – getting buy-in and closure at political level, including sign off for funding

- minimising reputational risk to the authority and defending decisions

- ensuring lessons are identified and addresses, (for example, by updating recovery plans), and shared with others who may find them useful

Media and communications

- maintaining good relationships with the media and public

- supporting the communication effort and assisting with the media in getting messages to the community, for example by giving interviews to the press

- assisting with VIP visits, ensuring that they are sensitive to the needs of the community

- supporting and assisting those affected in how they engage with media interest

Longer-term regeneration

Long after media interest has gone, there will still need to be a long term commitment to ensuring that the recovery of an area continues. In the longer term, elected members may be involved in:

- approving regeneration issues

- consultation on rebuilds or modernisation

- supporting business change in the community

- ensuring community cohesion in the community affected

- considering the need for longer term accommodation

- meeting MPs/AMs/MSPs/MLAs/MEPs to lobby for financial aid

- getting involved in appeal funds and memorials

- repairing and reconstructing the affected community

- ensuring that the lessons identified are applied to emergency/recovery plans and procedures and are shared with others who may find them useful

- by providing input into the humanitarian assistance effort and providing a public interface at Humanitarian Assistance Centres (HACs) (see the Needs of People – non-health topic sheet)

- anniversaries and commemoration

Involvement of elected members within the recovery effort need not just be limited to the elected members whose ward an incident has happened in or whose portfolio area it falls under. As community representatives for their wider area and given the complex, multi-agency nature of recovery and its impacts, all elected members could get involved.

As members of their community, both elected members and local authority staff may themselves be affected by an incident.

Local authorities

The local authority should ensure that its elected members have all the information they need to work effectively during the recovery phase, for example through training and briefing. This will enable them to effectively contribute to incidents and facilitate a return to a new ‘normality’.

Elected members should be involved in planning, training and exercising of plans to ensure that they are familiar with the recovery plans and arrangements and clear about what is expected of them in an emergency.

Training

Training and guidance could be given to elected members to help ensure that they are prepared for assisting in emergencies and in the recovery phase. Such training could focus on developing their awareness to ensure that they understand:

- civil protection legislation, including the Civil Contingencies Act (CCA) and the duties of responders under the CCA

- civil protection and emergency preparedness procedures

- locally identified risks and potential impact to local area / infrastructure

- the remit of elected members during the recovery phase and what is expected of them, ensuring that they are aware of what their role and responsibilities will be in an emergency, including their role within the Community Recovery Committee or RCG. This may also include clarifying what they might expect if they are to ‘approve’ the recovery strategy. Note that the normal political processes and structures will still apply in the recovery phase. Some Members may sit on both the Community Recovery Committee and their normal committees

- the difference between the response phase and recovery phase of an incident

- the role of other agencies within the recovery phase of an incident

- media awareness

- understanding of the central government recovery funding arrangements and principles

- how elected members should engage with other professionals, the media and the public

- the involvement of elected members in the delivery of key messages to the public, including how to communicate key messages to their communities

- how to give information, advice and guidance to the Community Recovery Committee and other agencies

- how elected members can scrutinise the recovery process

Elected members should be involved in exercises of recovery plans.

By training Elected Members in these areas in the planning stages, they will be prepared and clear of their responsibilities and role should an incident happen.

There may also be a benefit in training other agencies and organisations on the roles and responsibilities of elected members so that they are aware of their function within an emergency.

Elected members have a role as Cabinet members within their normal local authority duties and in doing this, give strategic direction and decide policy. They scrutinise decisions of officers and other committees and suggest improvements. They will ultimately scrutinise actions affecting the functions of Councils at all levels (including County/Unitary/District/City/Parish/Town/Community) so they will need to be kept well informed with accurate and up to date information to enable them to make credible and well informed judgements.

The Emergency Planning College provides training on crisis management and emergency planning, including an Introduction to Civil Protection and Recovering from Emergencies courses. It runs on-demand courses aimed at elected members which are delivered locally as and when requested by local authorities.

Briefing

There is a need to engage with elected members regularly throughout an emergency, from the planning phase, to the response phase and throughout the recovery phase. Elected members should be briefed thoroughly and regularly on the activities of the agencies involved during the recovery process.

Regular briefing is also important in ensuring that elected members sustain their community involvement and are able to communicate effectively and appropriately with agencies, the media and the public.

Elected members also need to be aware of other issues that may arise, and for which the local authority may be responsible or impacted, including:

- civil litigation

- criminal proceedings

- public inquiries

- impacts on council budgets (see the Financial impact on local authorities topic sheet) and loss of income for the council

- impacts on local authority performance targets (see the Impact on local authority performance targets topic sheet)

- insurance

- claims to the government

- long term effects on the community including long-term health and psychosocial effects

- lmpact on the local economy and business regeneration

Devolved Administrations

In Northern Ireland, different central and local government structures mean that district councils (the only level of council in Northern Ireland) have fewer service delivery functions than their counterparts in Great Britain, and functions such as social care are delivered by central government departments and their agencies and NDPBs. Northern Ireland civil contingencies legislation, the roles and responsibilities of individual organisations in relation to recovery, and the arrangements for co-ordinating the multi-agency recovery process differ from those in Great Britain. Nevertheless, the district councils play an important part in facilitating recovery at local level and the principles set out in this Topic Sheet offer a helpful indicator of the role which elected members of district councils can play as interfaces between council recovery arrangements and the community. Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive Ministers also have a very direct involvement with their communities and can similarly link with other service delivery organisations, within local structures and recovery arrangements.

Case studies (incidents and exercises)

Other documents

List of contacts

- Communities and Local Government

- Local Government Association

- Society of Local Government Chief Executives (Solace)

VIP visits and involvement

Background and Context

Following any emergency, it is likely there will be a desire for VIPs to visit the scene and to provide support to the affected community. Such visits may include members of the Royal Family, Ministers and MPs, faith leaders, other dignitaries or celebrities. Visits often take place during and immediately after the response phase, but may also be followed up in the recovery phase to provide continued support to affected communities and to observe progress on recovery.

The benefits of such visits include raising and maintaining awareness of the emergency, reinforcing messages of thanks, providing visible support to the community, helping to ‘fast-track’ some aspects of recovery, and giving positive media messages around the return to ‘normality’.

Key to the success of any such visit is community engagement with the planning of the visit and the decisions around the programme. For example, Faith Leaders may provide significant spiritual support to affected communities and such visits can also provide an important focus for reconciliation and developing community cohesion. However, it is important to assess the impact of any visit on the community to ensure it does add value.

Therefore, early and ongoing communication between local and regional partners, the affected community and the potential visitor is vital to ensure the benefits are maximised. Elected members can play a key role in this decision making process, reflecting the needs of their communities.

Policy and guidance

England

There is limited guidance available on the nature of visits and who are the most appropriate individuals to engage in the longer term recovery. Some guidance on the role of the Government Office in organising visits is described in Emergency Response and Recovery.

The choice of visitor can be by local determination, although Ministers and senior officials may also approach the communities after an emergency. Government Offices can provide advice and, importantly, a link to government departments to ensure assistance in development of programmes for visits and assistance in maximising their benefit.

Wales

The Welsh Assembly Government will need to be involved in any visits to Wales by the Royal family, UK Ministers or foreign dignitaries.

Scotland

[TBC]

Northern Ireland

[TBC]

Roles and Responsibilities

Local and Regional

Local partners, including the voluntary and faith communities, will wish to consider the appropriate visitors/support which may best focus the needs of the community and raise and maintain the necessary profile of the aftermath of the emergency. As the recovery proceeds, then the focus of such visits may change, from sympathy and gratitude to the responders, to more focus on the recovery and return to ‘normality’ for the community.

Both the community and the VIP will wish to maximise the benefit of any visit and ensure that a visit is neither divisive not overly onerous on the community. In considering any visit, especially where there may be an effect on community cohesion, it is important to assess the impact of the visit and to advise whether or not it would add value.

Lead Government Department

Where visits are by Ministers, the Lead Government Department would be responsible for arranging the visit, with local organisation done through the Government Office. Press and media liaison is organised via the COI News Distribution Service.

Royal visits are co-ordinated by the Royal Household through the Lord Lieutenant’s Office (there is one per LRF area). Details of the role and function of the Lord Lieutenant.

For Royal visits, press and media liaison is dealt with by the relevant Royal Household.

In some circumstances, it is possible that a foreign VIP (ie. Head of State / Prime Minister / Foreign Minister) may wish to visit the UK after an emergency, particularly if foreign nationals were affected. In this instance, the Visit Team in the Protocol Directorate of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) would be able to offer any logistical assistance required to the VIP. This could involve managing the visit from arrival to departure, any hospitality and transport. The desk in the FCO would set up any necessary calls with officials and would expect to be in contact with the Foreign Mission in London about arrangements.

Other Government Involvement

For Ministerial visits, organisation of the visit on the ground will be undertaken by the Government Office in partnership with the Minister’s Private Office, and with local organisations, to determine an appropriate programme for the visit.

Devolved Administrations

Any visit by a UK Minister to a devolved region is carried out in consultation with the Devolved Administration concerned.

Wales

Visits of UK Ministers and members of the Royal family to Wales need to be arranged in conjunction with the Public Administration Unit and Press Office of the Welsh Assembly Government. Visits by Welsh Ministers will be arranged between policy Departments, Ministerial Offices and the relevant responder agencies.

Scotland

Royal visits are co-ordinated by the Royal Household through the Lord Lieutenant’s Office

For Ministerial visits, organisation is undertaken by the Scottish Executive

Northern Ireland

[TBC]

Funding

Costs of Ministerial and associated visits are covered by the relevant Government Department.

Security costs for Ministerial and Royal visits fall to the police.

For visits by foreign VIPs, the Protocol Directorate (FCO) would probably meet the costs for a Guest of Government status, under special circumstances and as a one off, but this agreement would depend on the VIP’s status and other criteria at the time.

Devolved Administrations

Wales

Security costs for VIP visits to Wales fall to the Police.

Scotland

Scotland – funding is the same as England.

Northern Ireland

[TBC]

Case Studies (Incidents and Exercises)

Other Documents

List of Contacts

Impact on Local Authority Performance Targets

Background and Context

Currently, local authorities are set targets by several Government Departments in respect of a range of their activities. Targets can include a requirement that a certain minimum standard is achieved, eg at least 20% of all pupils to obtain 5 or more GCSEs (known as ‘floor targets’) or they may be aspirational, eg. 65% of pupils to obtain 5 or more GCSEs in 2008, rising to 68% in 2009, etc.

Some incidents, such as the Carlisle floods and the explosion at the Buncefield oil depot, have shown that, due to resource pressures and other consequences, local authorities have been unable to meet certain performance targets.

Local authorities who administer Housing and Council Tax Benefit report quarterly against a number of performance measures. When an incident affects a local authority’s ability to meet certain targets, all circumstances will be taken into consideration when monitoring performance, carrying out inspections or making judgements on performance in the wider context of the Comprehensive Performance Assessment.

Policy and Guidance

England

A new performance framework for local authorities and their partners in England is being introduced in 2008-09. The framework has been designed to:

- strengthen accountability to citizens and communities

- give greater responsibility to local authorities and their partners for securing improvements in services

- provide a better balance between national and local priorities

- improve arrangements for external assessment and inspection

Under the new framework, there will be a revised Local Area Agreement (LAA) process through which central Government and Local Strategic Partnerships (LSPs) will agree and manage a limited number of performance targets for each local area.

The focus will be on the 150 single tier (unitary) authorities and county councils. District authorities will report on progress against their activities to their county council rather than direct to central Government or the relevant Government Office for the Region. Where appropriate, county councils will include this performance information in their annual performance report to their Government Office (eg when there is an improvement target in a LAA that relate to a service for which a district authority has responsibility, eg housing).